Benjamin Harris

America’s First Editor/Publisher

of

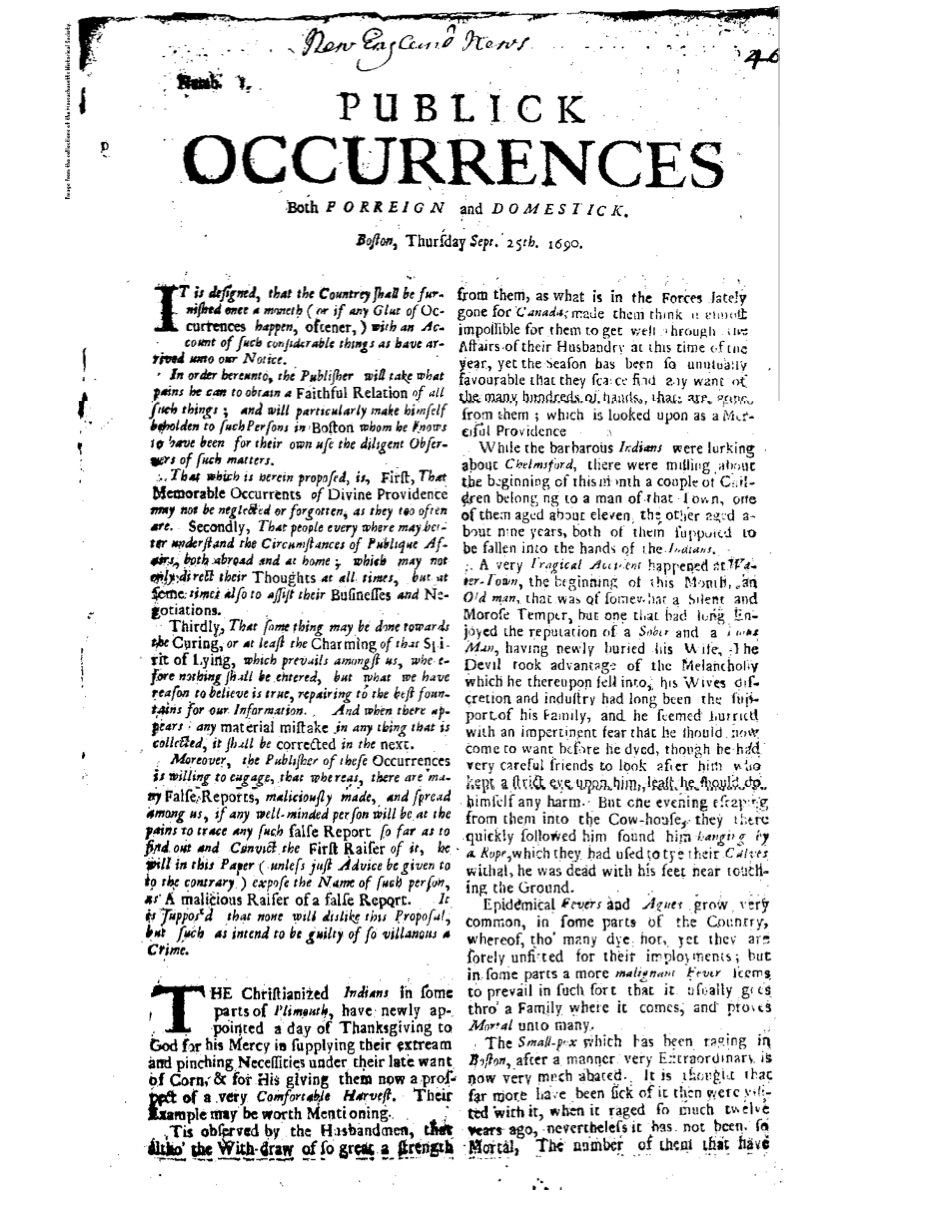

PUBLICK OCCURRENCES

Both FORREIGN and DOMESTICK

Boston, September 25, 1690

Benjamin Harris (1673-1716) was a

vocal anti-Catholic London pamphleteer and editor of London’s Domestick Intelligence or News both from City and Country

which, it said, was “Published to prevent false Reports.” He was one of the “inventors”

of the fictitious 1678 “Popish Plot,” which alleged that Jesuits were planning to kill

King Charles II and install to the throne his Catholic brother. Harris was fined and

imprisoned several times and in 1686 he left with his family for Boston, where he opened

the London Coffee House (at today’s intersection of Washington and Court streets), in

which he printed and sold books. He published America’s first textbook, the hugely

popular New England Primer. Along with books, he was licensed

to sell “Coffee, Tea and Chucaletto”(most likely a chocolate drink).

On Sept. 25, 1690, he published

Publick Occurrences, a paper that measured 7.5x11.5 inches

and had text on three of its four pages--the fourth was left blank so the readers could

write their personal “news” or views before they passed the paper to neighbors. (Could

this have been a first attempt at blogging?) Its circulation was not known but above its

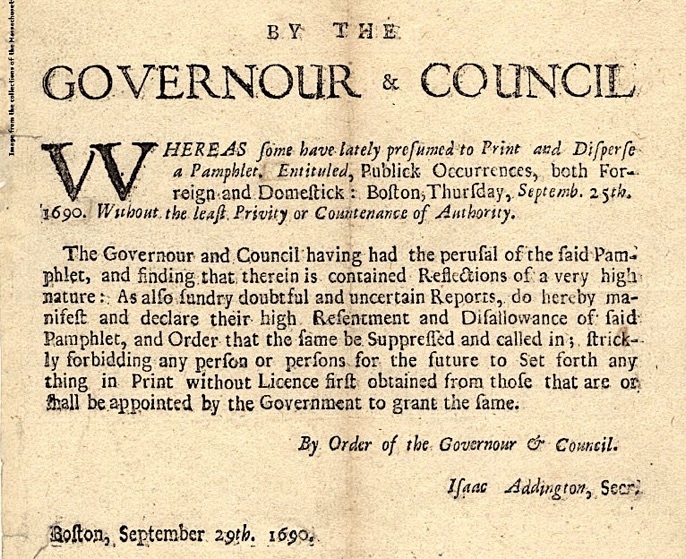

nameplate the only surviving issue has a hand written number “462.” Publick Occurrences was shut down four days after its first and

only issue by the “governour and council” because, the order said, the newspaper was

printed without permission and contained “doubtful and uncertain Reports.” (See copy of

the letter below.) The issue’s most controversial story was likely the one that alleged

that the king of France “used to lie with the Son’s Wife.” Such a story might have

seriously jeopardized Franco-British relations.

Harris’ first news item was about

the “the Christianized Indians in some parts of Plimouth,” who “have newly appointed a

day of Thanksgiving to God....” The paper also included such news items as several

confrontations among Indians and European settlers in New England, a Watertown farmer

who committed suicide because he was depressed over his wife’s death, items about

“Epidemical Fevers” and “Small-pox,” a “Disaster by Fire” that destroyed many houses

around the “South-Meeting-House” and “near the Mill-Creek,” and a report about a failed

“Western Expedition against Canada.” News items were not separated by headlines, but by

blank spaces and indentations.

But Harris’ publishing genius became

evident through his impressive foresight about his journalistic undertaking. In his

first section of text, which appeared in italics under the paper’s name and before the

actual news stories, he laid out his principles and goals. ( See photos below.)

Harris promised “the Country shall

be furnished once a moneth (or if any Glut of Occurrences happen, oftener) with an

Account of such considerable things as have arrived unto our Notice.” He also promised

to “take what pains he can to obtain a Faithful Relation of all such things” and would

rely on “such persons in Boston whom he knows to have been….diligent Observers of such

matters.”

“Memorable Occurrences of Divine

Providence may not be neglected or forgotten, as they often are,” Harris wrote, and

promised to do something “towards the Curing, or at least the Charming of that Spirit of

Lying, which prevails amongst us.”

Harris pledged that his paper’s news

stories would help people “better understand the Circumstances of Publique Affairs, both

abroad and at home” and never print anything except “what we have reason to believe is

true.”

Finally, Harris wrote, if a mistake

is made “it shall be corrected in the next” issue, and promised that those who spread

“False Reports, maliciously made” would be exposed as having committed a “villainous”

crime.

These are important commitments,

promises and ethical parameters that govern journalism even today. For Harris to have

made them in 1690 is as inspiring as it is hard to believe. But he did, and he set the

bar high for those who followed.

It is unfortunate that he did not

have a chance to practice what he promised. Issues of his paper were destroyed, except

for one copy that was sent to England and today can be found in the London Public

Records Office. In 1692 Massachusetts Gov. William Phipps appointed Harris as the

state’s printer. Harris returned to London in 1695, where he published the London Post, 1699-1706. He died in 1716.

***

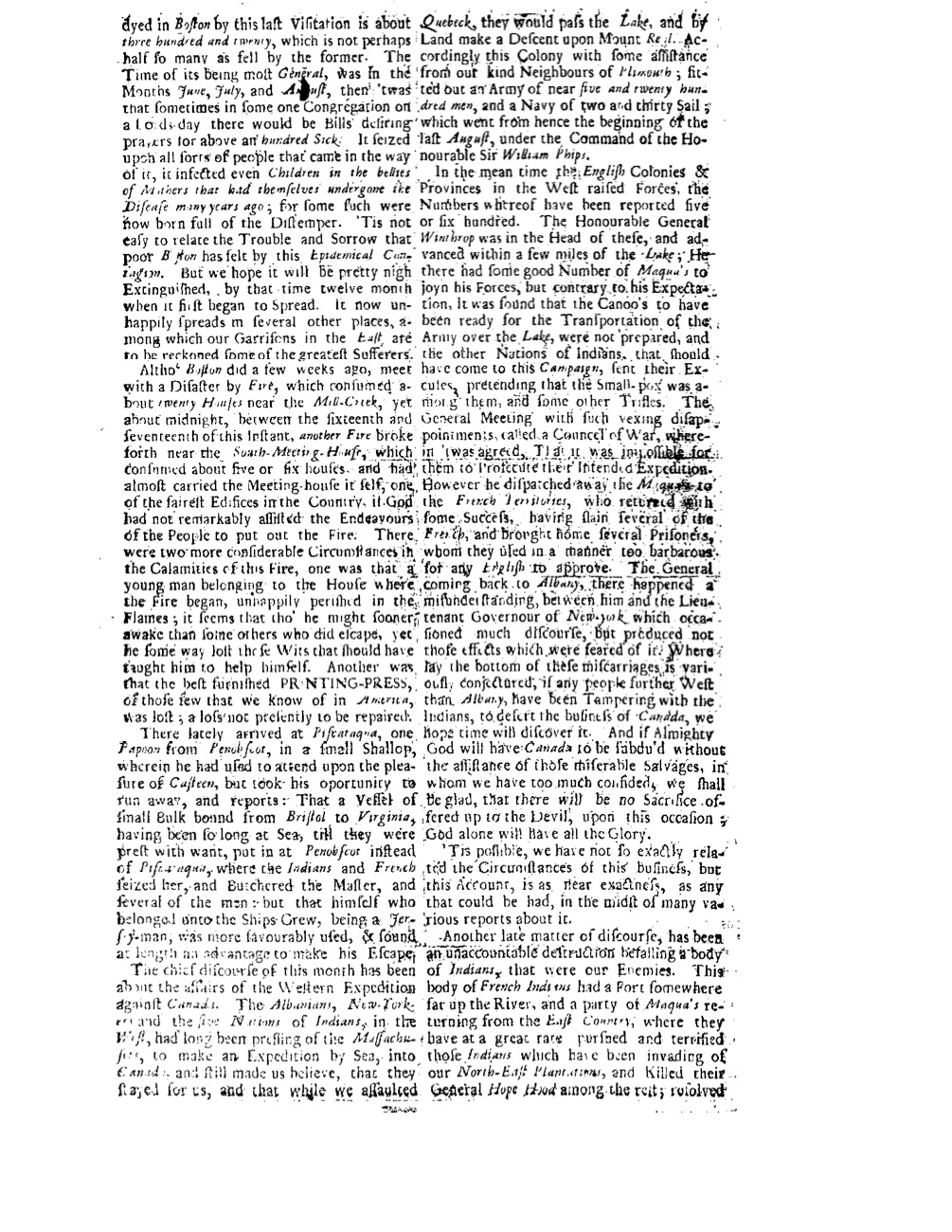

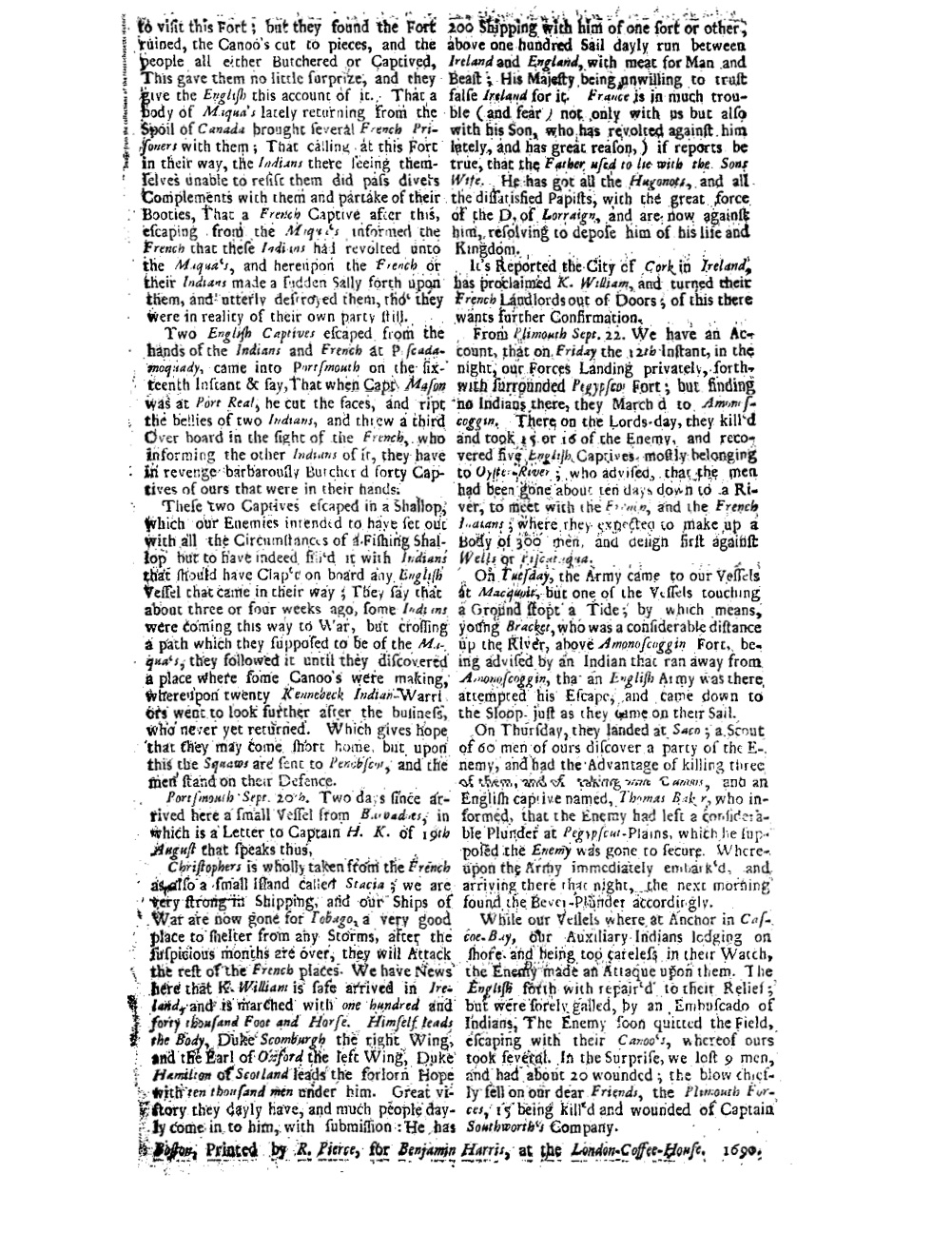

Here are the three pages of the

original Publick Occurrences--the fourth page was blank.

Below them is the letter outlawing the newspaper.