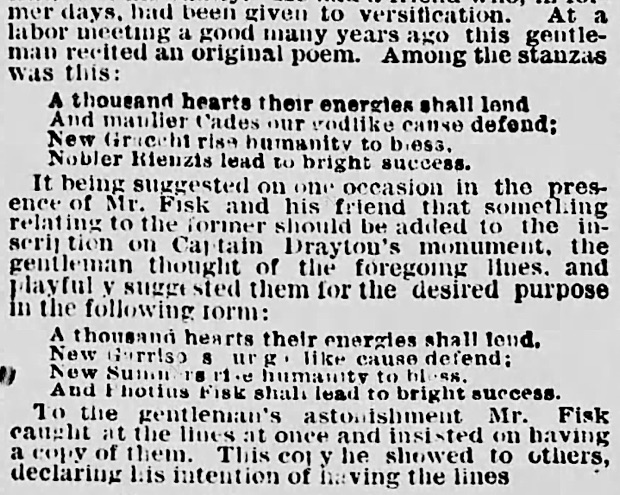

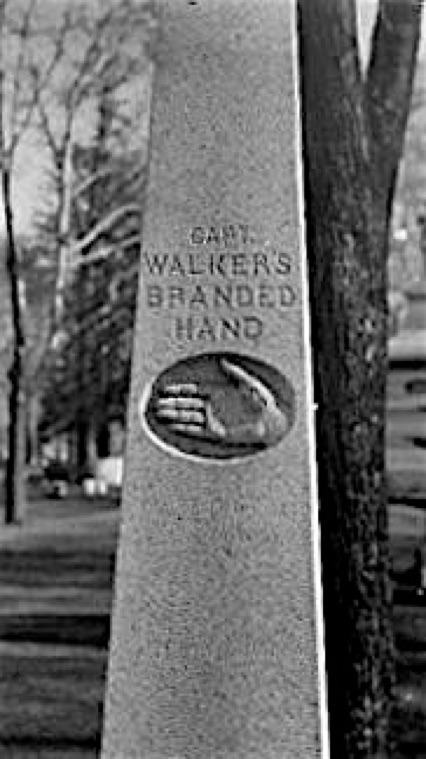

Above, New York Times article (June 16, 1878), about Fisk’s donation to a granite monument for abolitionist Capt. Jonathan Walker’s grave (left) in Muskegon, MI. Walker’s hand was branded in Florida in 1844 as punishment for his transporting slaves to the Bahamas to be freed. The branding of “SS” stood for “slave stealer.” John Greenleaf Whittier immortalized Walker’s action in his 1846 poem “Branded Hand” through the verse: "Then lift that manly right hand, bold ploughman of the wave! Its branded palm shall prophesy, 'Salvation to the Slave!'" (Photo on right, African American Odyssey, Library of Congress.)

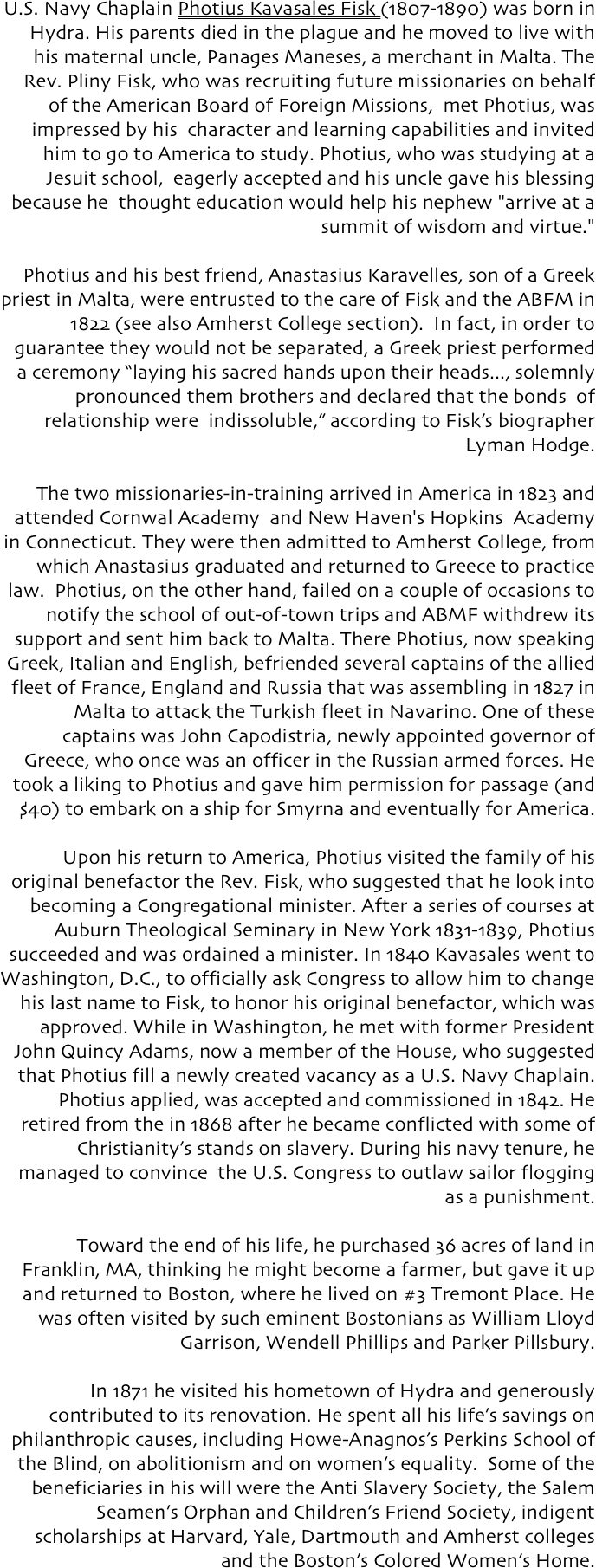

Left, excerpt from the 1871 Fisk passport application. He is described as 5’ 3.5” tall, with “high” forehead, “hazel” eyes, “Grecian” nose, “small” mouth, “medium” chin, “grey” hair, “dark” complexion and a “thin” face... [First legal confirmation of the existence of a Greek nose type!]

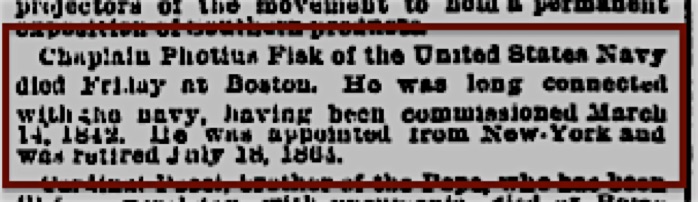

New York Times Photius Fisk obituary of Feb. 9, 1890.

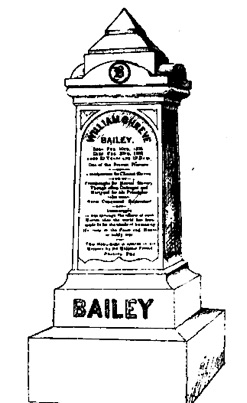

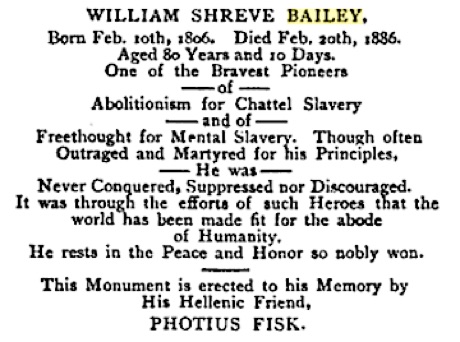

W. S. Bailey was a mechanic-turned publisher of several abolitionist papers, most notably the Newport News and the Free South, in Kentucky starting in 1839. His offices were burned down several times and he was persecuted for variety of causes throughout his life. He finally moved to Nashville, TN, where he died in 1886. His life story so moved Fisk that he erected an elaborate tombstone honoring Bailey with the epigram that ends with “This Monument is erected to his Memory by His Hellenic Friend PHOTIUS FISK.”

Photius Fisk in Boston

In a long article Feb. 4, 1883, under the headline “Rev. Photius Fisk, U.S.N., A Queer Compound of Philanthropy and Pessimism,” The Boston Globe gave a detailed description of “An Eccentric Chaplain Whose Life Belies His Philosophy.”

The article’s author described Fisk as a “Boston character.... a short, slim, frail figure moving rapidly along with quick elastic step.” He was known and loved by many, the article said, “especially among the poor, lowly and unfortunate.” The article described him as having “nervous gray eyes, thin face, sharp features, something between a saffron and bronze complexion and long white locks, not hanging but drawn up on either side over a head bald on top.”

The article traced Fisk’s life from Hydra, to Smyrna, to Malta and America and focused on his life in Boston. It said his exposure to slavery in Martinique turned him to a passionate abolitionist, which caused his biographer, Lyman Hodge, to write that Fisk was an “Abolitionist before he saw America.”

After he arrived in America, Fisk was educated at the Mission School, Cornwall, CT, (1822-23); the Hopkins Academy, New Haven (1823-25), CT, and the Amherst Academy, Amherst College (1825-27). His Boston Daily Globe obituary, Feb. 10, 1890, said that for a time the American Board of Foreign Missions entrusted him to the care of distinguished Presbyterian minister and social reformer the Rev. Lyman Beecher of Litchfield, CT, father of Harriet Beecher Stow, author of the famous abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. His final educational institution was the Auburn (NY) Theological Seminary (1831-39), which qualified him to serve as a minister.

Fisk’s anti-slavery positions were not helpful to him in his naval career and his objection to flogging as sailor punishment exacerbated his situation. But he dedicated himself to helping the weak around him, the poor, the orphans, African Americans, abolitionists, women, girls and suffragists. He associated with all the major slavery opponents of his time and is alleged to have fallen in love with the daughter of Gerritt Smith, a prominent New York politician, reformer, and abolitionist. But when she turned him down, Fisk was so devastated he never recovered, wrote George Perros, archivist at the U. S. Bureau of Archives in the Greek American Review, August 1991.

By the time Fisk retired, his frugal lifestyle had yielded more than $40,000 according to Hodge ($1.3 million today although some say he had something like $4 million) in savings and investments, which he then spent on his favorite causes. He invested in government bonds, counted every penny and fought for every penny he was owed. But “he was honest as the day and generous as he can live,” the Globe article said. He mistrusted the Greenback movement because he thought it would undermine the government bonds he owned, and that damaged many of his friendships, including the one with Wendell Phillips.

The Globe article said Fisk appointed several executors to his will, including at one point suffragist and Woman’s Journal editor Lucy Stone, to ensure that “poor colored youth” of Harvard, Yale, Amherst and Williams received sustained help. He would regularly help the Poor House and the Orphan Males Asylum in Athens and construction projects and charities in his native island of Hydra. The Photius Fisk Trust is still active today in Providence, R.I.

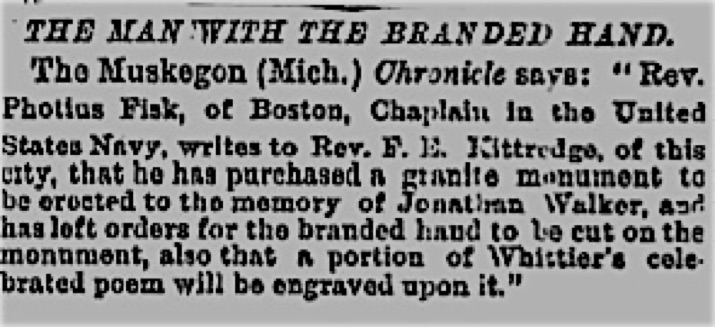

He was an eccentric man who disliked marriage and litigation, the Globe 1883 article said. But he was “susceptible to flattery.” The incident of the poem below is characteristic of this trait.

In the late 1850s Fisk became disillusioned with parts of the Old and New Testaments that he thought “not only permitted but approved and provided for…. human bondage…” This was something that he could not tolerate. His biographer Hodge wrote that Fisk “said within himself ‘If slavery is any part of Christianity, then I am not a Christian.’” That effectively ended Fisk’s chaplaincy. He retired with the rank of captain in 1864 and his retirement became official in 1868.

At the end of his life, Fisk lived on the fourth floor of 613 Tremont St. in Boston. He died on Feb. 7, 1890 and was buried in Salem’s Harmony Grove Cemetery.

Fisk’s grave