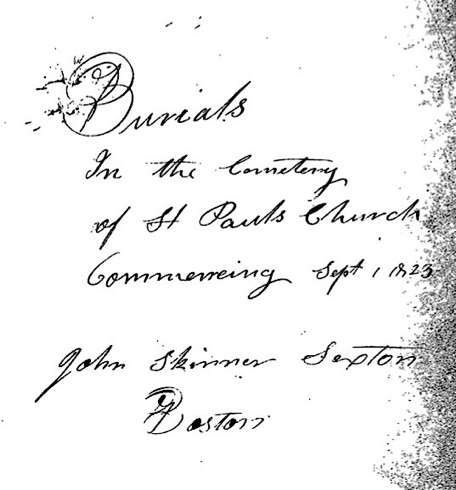

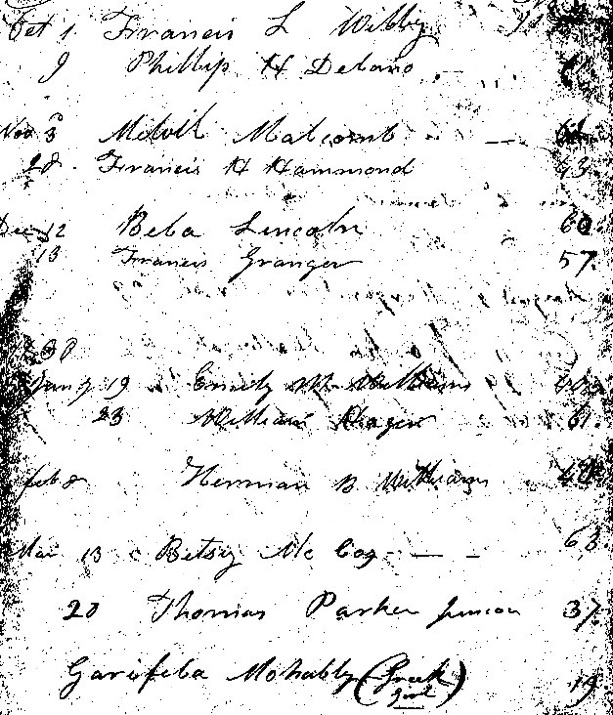

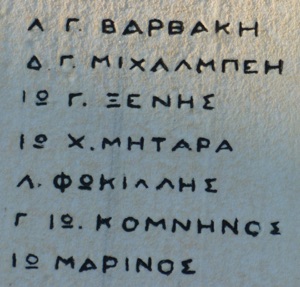

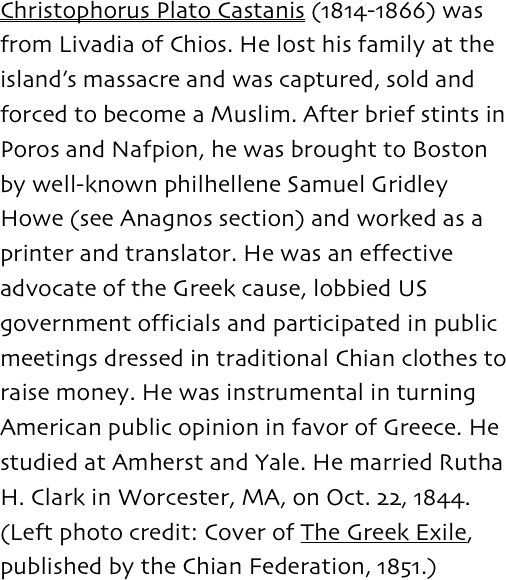

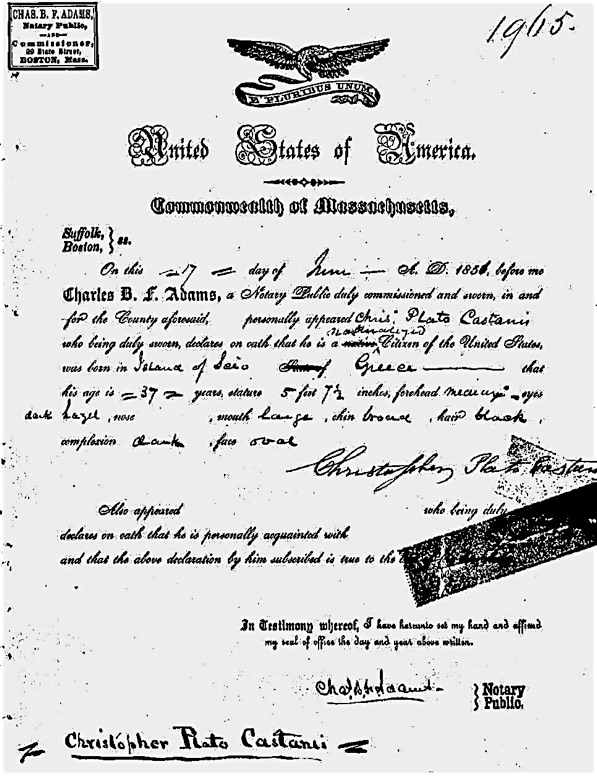

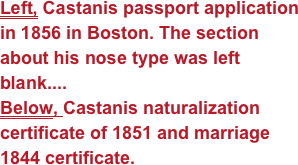

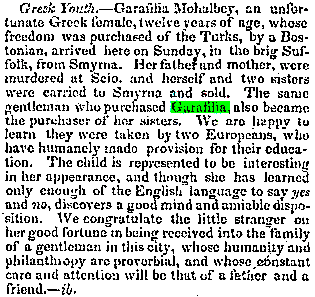

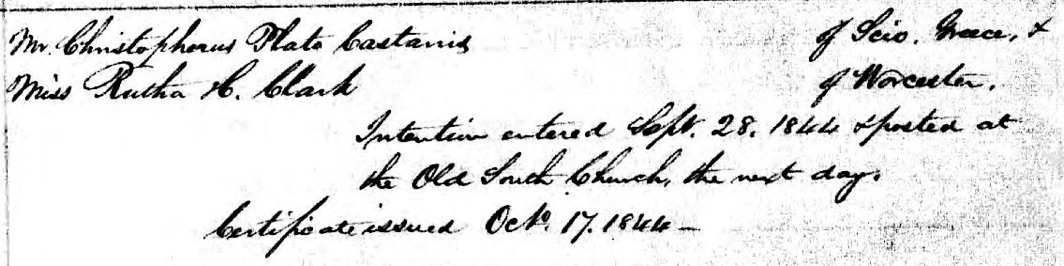

Garafilia Mohalbi(y) (Γαρυφαλλιά Μιχάλμπεη) (1817-1830) was born to a prominent family on the island of Psara (Ψαρά). Her parents and siblings were killed in the 1824 Psara massacre by the Turks. There are many stories about how she survived (i.e. her mother pushed her in a row boat away from the island), but in 1824 she found herself working as a maid of a Turkish family in Smyrna.

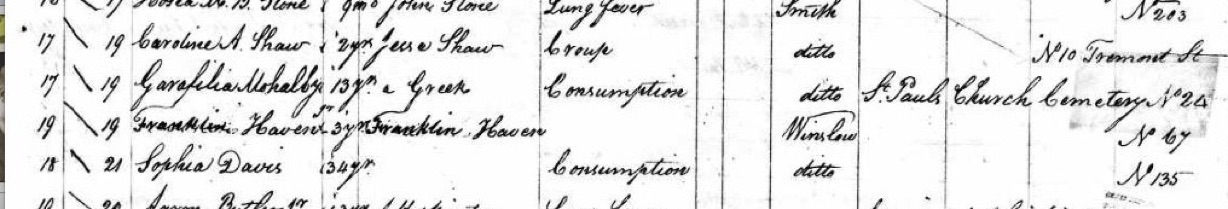

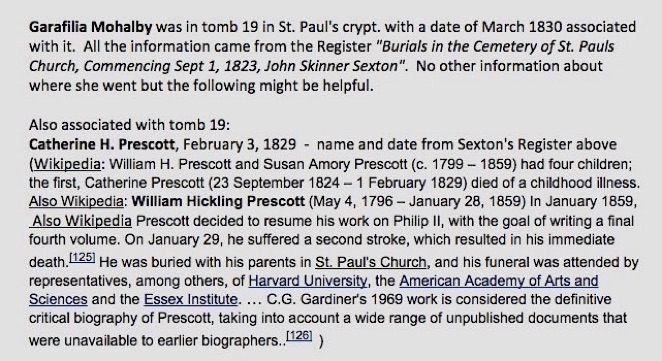

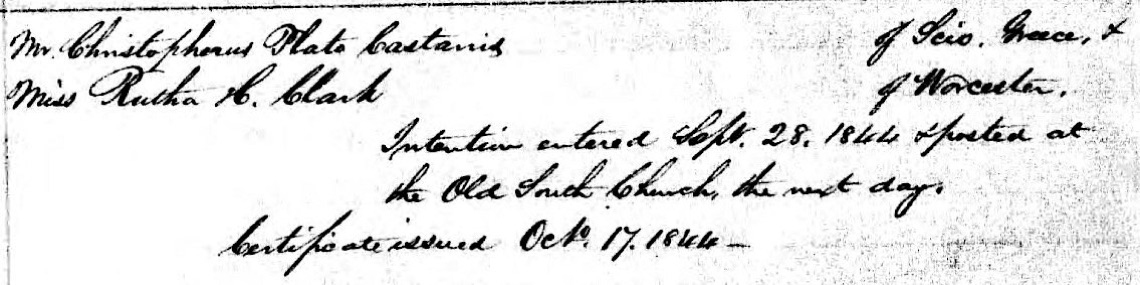

At a Smyrna bazaar in 1827, she met American merchant/consul Joseph Langdon and begged him to rescue her. He “ransomed” her and sent her to his Boston family to be educated. Garafilia attended the Ursuline Convent School in Charlestown, but died from tuberculosis March 17, 1830, at age 13. Her story along with her beauty, intelligence and sweet disposition touched America.

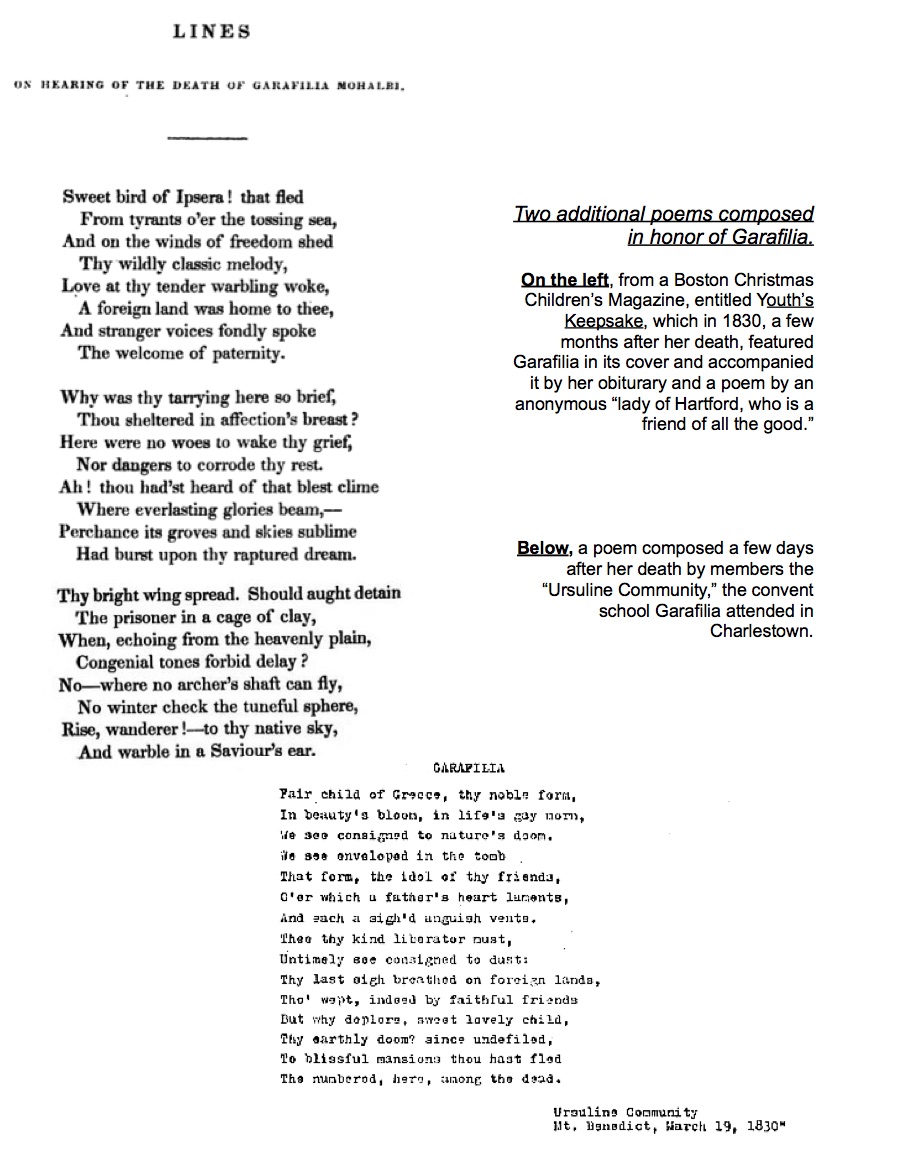

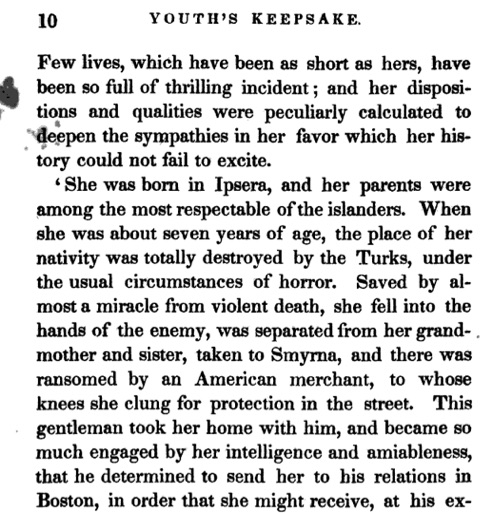

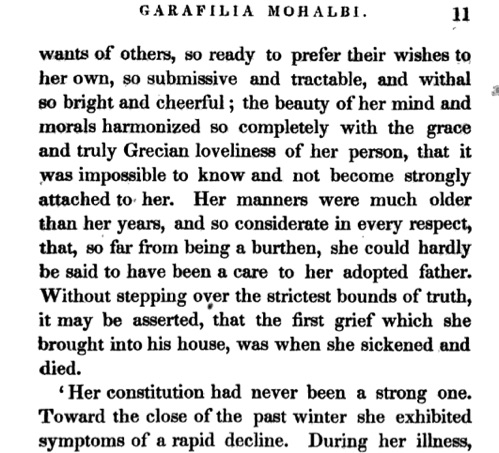

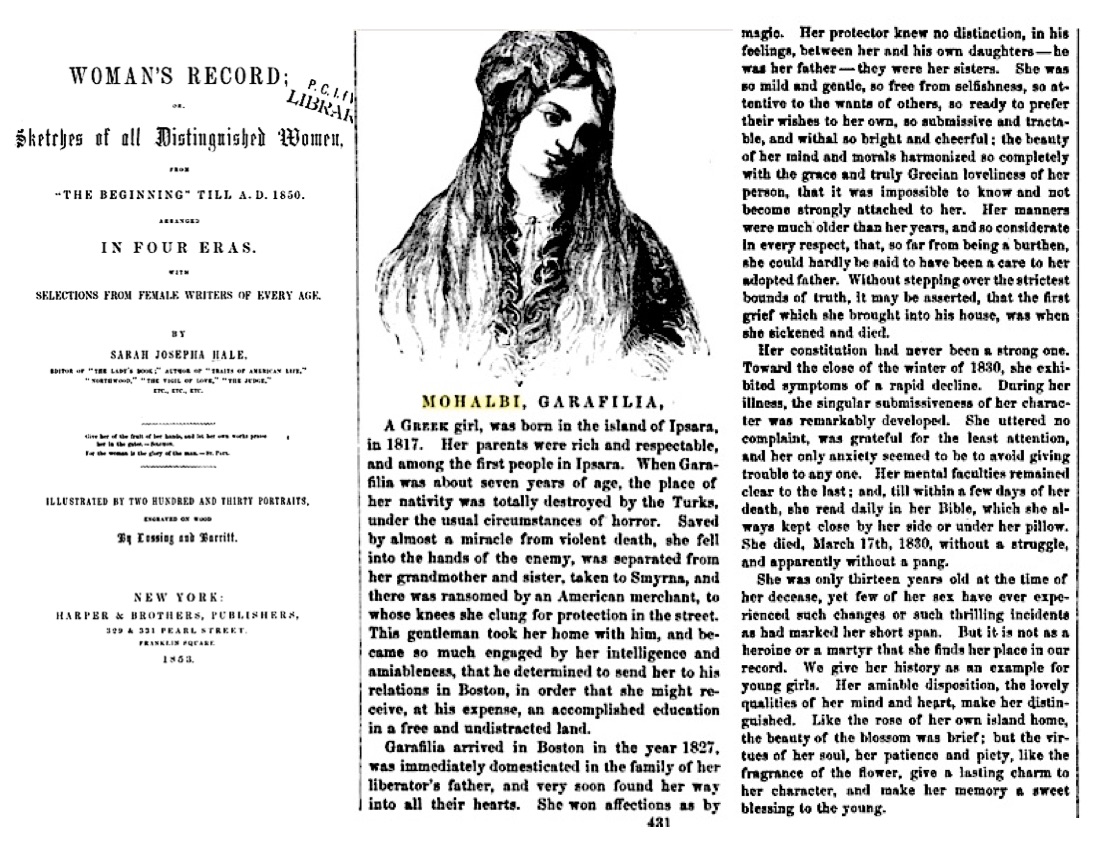

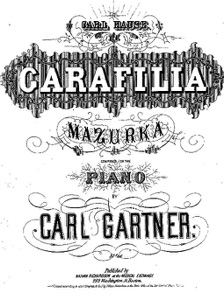

New York artist Anne Hall painted Garafilia’s portrait as the “Greek Girl,” Boston composer Carl Gartner wrote the Garafilia Mazurka and popular Connecticut author/poet Lydia Sigourney wrote a poem dedicated to the “Sweet bird of Ipsara.” America’s first woman magazine editor, Sarah Josepha Hale, dedicated to Garafilia a chapter in her 1853 book, Woman’s Record, Sketches of All Distinguished Women and Boston’s children’s magazine The Youth’s Keepsake used Garafilia as the cover story of its Christmas 1830 issue. Obituaries were written in several newspapers around the country and some families chose to give her name to their newborn daughters.

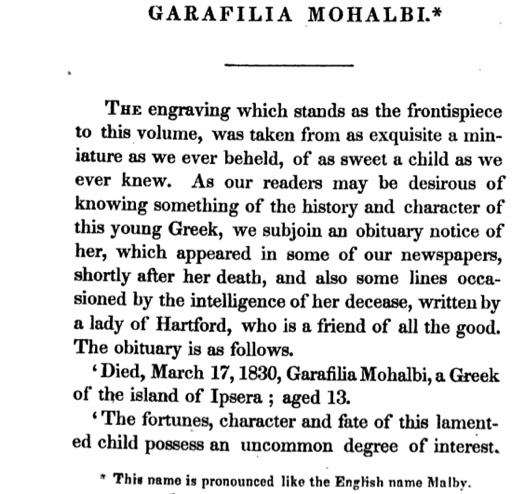

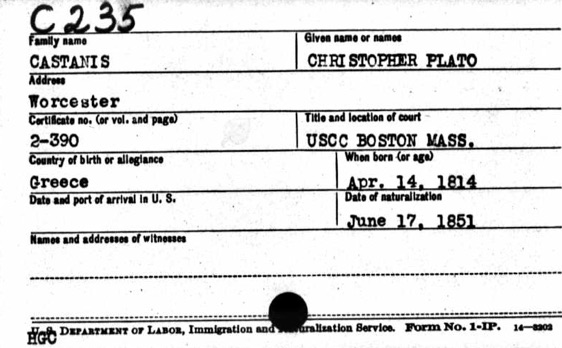

Garafilia was also the likely inspiration for the famous 1844 statue “The Greek Slave,” by Hiram Powers, one of the best-known American sculptors of the 19th century. Powers wrote “The Slave has been taken from one of the Greek Islands by the Turks, in the time of the Greek revolution, the history of which is familiar to all. Her father and mother, and perhaps all her kindred, have been destroyed by her foes, and she alone preserved as a treasure too valuable to be thrown away….” (“The Greek Slave,” in Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture, University of Virginia, 1998-2012, retrieved 4/5/2017). The statue became a powerful symbol in America’s abolitionist movement and Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote a sonnet about it.

Langdon’s “rescue” of Garafilia is described by one of his descendants, Louise Langdon van Agt, in her manuscript “The Humbler Bostonians,” held in the New England Historic Genealogical Society. Harriet Beecher Stowe in her 1854 book “The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” (Boston: Jewett, 1854, p. 303) alludes to Garafilia’s case by writing “I was in Smyrna when our American consul ransomed a beautiful Greek girl in the slave-market. I saw her come aboard the brig ‘Suffolk,’ when she came on board to be sent to America for her education.”

![Hiram Powers' Greek Slave

They say Ideal beauty cannot enter

The house of anguish. On the threshold stands

An alien Image with enshackled hands,

Called the Greek Slave! as if the artist meant her

(That passionless perfection which he lent her,

Shadowed not darkened where the sill expands)

To so confront man's crimes in different lands

With man's ideal sense. Pierce to the centre,

Art's fiery finger! and break up ere long

The serfdom of this world. Appeal, fair stone,

From God's pure heights of beauty against man's wrong!

Catch up in thy divine face, not alone

East griefs but west, and strike and shame the strong,

By thunders of white silence, overthrown.

— Elizabeth Barrett Browning [II, 302]](Garafilia,_Castanis_files/shapeimage_1.png)